Prof Mason

Liverpool Foot and Ankle Clinic

To book an appointment, either email or phone the number below or click the link.

E-mail: CVDWclerical@outlook.com

Contact Patient Liaison: 07717580737

Stress Fracture

What is a stress fracture?

A stress fracture is a small crack in a bone that develops gradually over time. Unlike a sudden break caused by an accident, stress fractures happen when a bone is repeatedly loaded without enough time to recover. This leads to tiny areas of damage that eventually weaken the bone and cause pain. There is also some cross over with a pathological fracture, where the break of bone occurs due to a weakness in the bone, unable to withstand normal forces.

Stress fractures are most common in the foot and ankle because these bones absorb large forces with walking, running, jumping, and standing for long periods.

Why do stress fractures occur?

Stress fractures usually develop due to a combination of mechanical stress and reduced bone recovery rather than a single cause.

Common contributing factors

- Sudden increase in activity (for example, starting running, increasing mileage, or changing training intensity)

- Repetitive impact such as running, marching, jumping, or dancing

- Inadequate rest or recovery

- Foot shape or alignment (high-arched feet, flat feet, cavovarus alignment)

- Poor footwear or change in training surface

- Muscle fatigue, which alters how forces pass through the foot

Bone health factors

- Low bone mineral density or osteoporosis

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Hormonal imbalance

- Low energy intake (relative energy deficiency)

- In women, menstrual irregularities and eating disorders (often referred to as the female athlete triad)

These factors reduce the bone’s ability to repair itself between periods of loading

Where do stress fractures occur?

Stress fractures in the foot and ankle are commonly grouped into low-risk and high-risk areas, depending on how reliably they heal.

Low-risk stress fractures

These usually heal well with activity modification:

- Calcaneus (heel bone)

- Cuboid

- Cuneiform bones

- Second to fourth metatarsals (midfoot bones)

- Distal fibula (outer ankle)

High-risk stress fractures

These are more prone to delayed healing or non-union:

- Navicular (midfoot)

- Talus (ankle bone)

- Medial malleolus (inside ankle)

- Base of the fifth metatarsal

- Hallux sesamoids (bones under the big toe)

- High-risk stress fractures often need

closer monitoring and sometimes surgery

What are the symptoms?

Stress fractures usually cause gradual and progressive symptoms, rather than sudden severe pain. Because the early signs can be subtle, they are often mistaken for a muscle strain or “overuse pain,” which can delay diagnosis.

Early symptoms

In the early stages, you may notice:

- A dull ache in a specific area of the foot or ankle

- Pain that starts during activity (walking, running, exercise)

- Pain that improves with rest

- Discomfort that feels vague or difficult to pinpoint at first

At this stage, everyday activities may still be possible, but symptoms often recur each time activity is repeated.

Progressive symptoms

If loading of the bone continues, symptoms typically worsen:

- Pain occurs earlier during activity and becomes more intense

- Pain may persist after activity has stopped

- Increasing localised tenderness when pressing on the bone

- Reduced tolerance for walking, running, or standing for long periods

- A feeling of weakness or “giving way” in the foot or ankle

Pain usually becomes more well localised as the injury progresses, often allowing patients to point to one exact spot that is painful.

Later or more severe symptoms

With further progression:

- Pain may be present even at rest

- Pain may occur with normal daily walking

- Swelling, warmth, or mild redness may appear over the affected area

- Limping or altered walking pattern may develop

- In some cases, pain may disturb sleep

At this stage, continuing activity significantly increases the risk of the fracture worsening or progressing to a complete break.

Symptoms vary by location

The exact symptoms can differ depending on which bone is affected:

- Heel (calcaneus)

Deep heel pain, often worse with walking or running; squeezing the heel from the sides may reproduce pain. - Midfoot (navicular, cuboid, cuneiforms)

Pain on the top or inside of the foot, worse with push-off; often minimal swelling but very localised tenderness. - Metatarsals (forefoot)

Forefoot pain that worsens with weight-bearing; sometimes swelling on the top of the foot. - Ankle bones (talus, medial malleolus)

Deep ankle pain, sometimes felt during walking on uneven ground or with ankle movement. - Sesamoids (under the big toe)

Pain beneath the big toe, especially during push-off, running, or wearing thin-soled shoes

How is a stress fracture diagnosed?

Clinical assessment

Your clinician will ask about:

- Recent changes in activity or training

- Footwear and surfaces

- Nutrition and bone health

- Menstrual history (where relevant)

They will examine your foot and ankle alignment, tenderness, and gait.

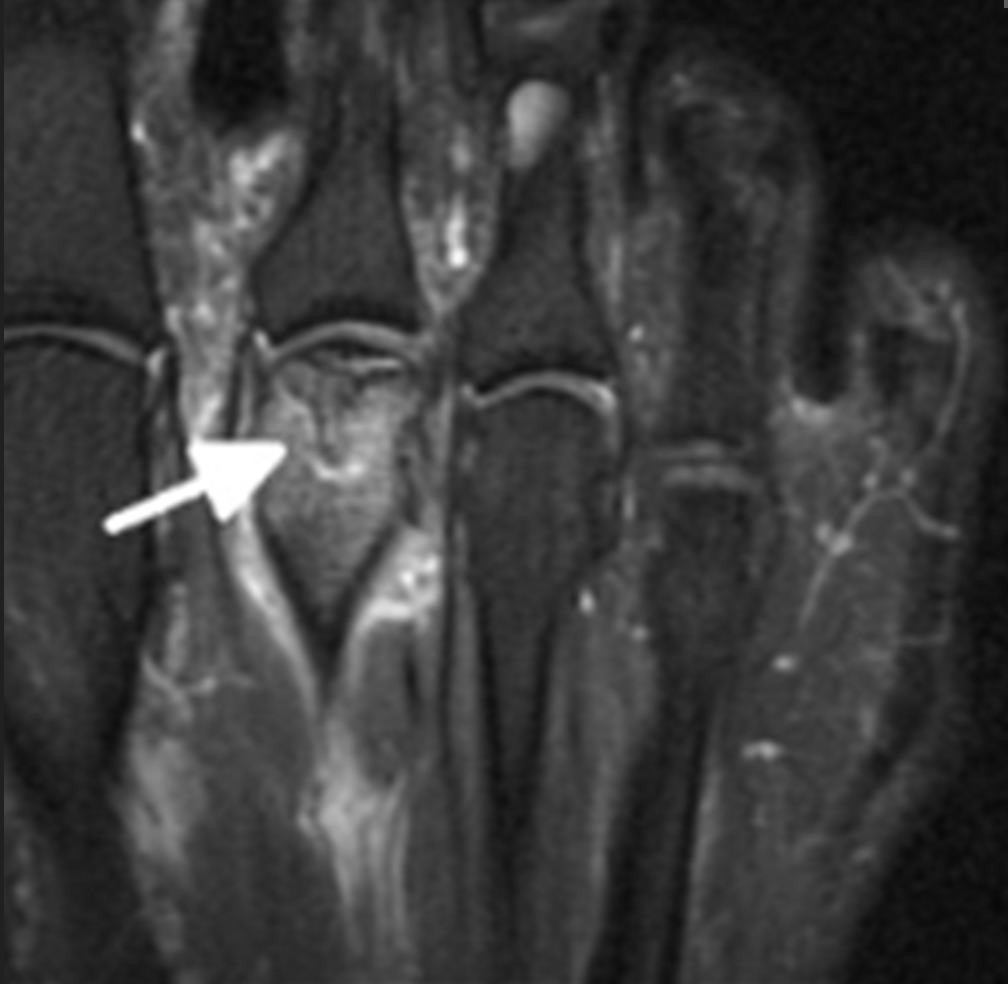

Imaging

- X-rays: often normal early on, but repeat x-rays after a few weeks can show the bone healing.

- MRI scan: the most sensitive test and often confirms the diagnosis

- CT scan: sometimes used to assess healing or fracture detail

MRI is particularly useful because it can detect early bone stress before a clear fracture line forms (bone stress reaction).

MRI is good at showing active and latent disease, especially in the early stages where X-rays are sometimes not useful

Non-surgical treatment

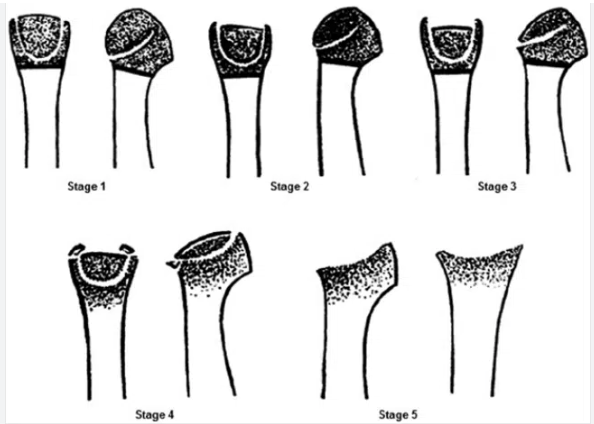

Non-surgical treatment is usually recommended for early stages of Freiberg’s disease (Smillie stages I–II) and for patients whose symptoms are mild or intermittent. The aim is to reduce pain, off-load the affected joint, and slow disease progression while the bone and cartilage attempt to recover.

Activity modification

Reducing activities that overload the ball of the foot is essential. This may include limiting running, jumping, prolonged standing, or high-impact sport. Complete rest is rarely necessary, but avoiding painful activities helps prevent further joint damage and allows symptoms to settle.

Footwear modification

Supportive footwear plays a key role in symptom control. Shoes with:

- A cushioned sole

- A stiff or rocker-bottom sole

- Adequate width in the forefoot

help reduce pressure through the affected metatarsal head. Thin-soled or flexible shoes tend to worsen symptoms and are best avoided.

Insoles and off-loading

Custom or prefabricated insoles can reduce load on the painful joint. These often include:

- Metatarsal pads or bars to shift pressure away from the affected toe

- Forefoot off-loading to reduce peak pressure during walking

Many patients notice meaningful pain relief with appropriate off-loading, particularly in the earlier stages.

Pain relief

Simple pain relief such as paracetamol or anti-inflammatory medication may help control symptoms, especially during flare-ups. These medications do not treat the underlying problem but can improve comfort while other measures take effect.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy focuses on:

- Improving foot and ankle mechanics

- Addressing calf tightness and forefoot loading patterns

- Gait advice to reduce pressure through the affected joint

While physiotherapy cannot reverse joint damage, it can help reduce symptoms and prevent compensatory problems elsewhere in the foot.

Immobilisation (selected cases)

In more painful early cases, a short period of reduced weight-bearing or use of a protective boot may be recommended. This is usually temporary and reserved for significant pain or flare-ups.

Expected outcomes

- Many patients with early-stage Freiberg’s disease improve with non-surgical treatment

- Symptoms may settle gradually over months rather than weeks

- Non-surgical treatment is less effective in advanced stages where joint collapse has occurred

Important points

- Non-surgical treatment aims to control symptoms and slow progression, not restore damaged cartilage

- Early diagnosis improves the chance of success

- Ongoing pain despite appropriate non-surgical care may lead to discussion of surgical options

Surgical Treatments

A wide range of operations have been described. The most commonly used and best-studied procedures are joint-preserving surgeries.

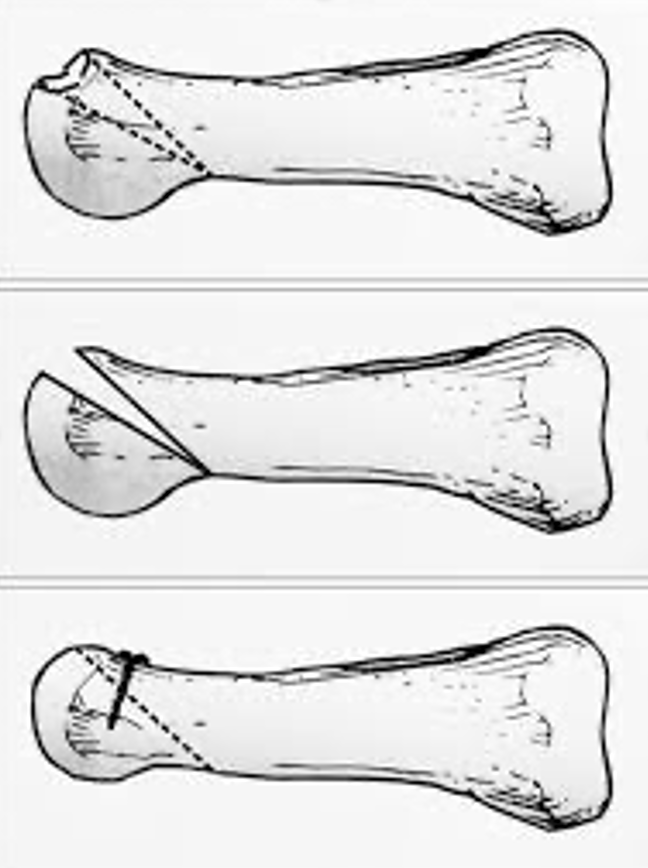

Dorsal closing wedge metatarsal osteotomy (DCWMO)

- A small wedge of bone is removed from the metatarsal

- This rotates healthier cartilage into the weight-bearing area

- Long-established technique with good pain relief

- Slightly shortens the metatarsal, which can affect foot mechanics in some patients

Autologous osteochondral transplantation

- A small plug of healthy cartilage and bone is taken from another joint (usually the knee)

- It is transferred to the damaged area of the metatarsal head

- Restores the joint surface without shortening the bone

- Associated with better movement, faster return to activity, and fewer complications in comparative studies

- Donor site problems are possible

Other procedures may be used in selected cases, including:

- Modified Weil osteotomies

- Microfracture or cartilage stimulation techniques

- Joint resurfacing or interpositional procedures (less common)

Recovery after surgery

- Usually protected weight-bearing in a boot initially

- Gradual return to normal shoes

- Physiotherapy to restore movement and strength

- Full recovery may take several months

- Most patients experience significant pain relief and improved function